Wittenberg - The Cradle of Protestant Reformation

When I decided to plan our trip to Germany around the Protestant Reformation, there was not a shred of doubt that I wanted to spend a few nights in Wittenberg. Martin Luther is among the most pivotal figures in European history; many cities celebrate their association with the famed reformer but proclaim themselves as Lutherstadt, the “Luther city.” However, only two incorporate that title into their official name: Lutherstadt Wittenberg and Lutherstadt Eisleben. Eisleben was the ancestral home and birthplace of Luther, and where Luther died in 1546. However, no other city has more to do with the Protestant Reformation than Wittenberg. This was where Luther taught, preached, and resided most of his life.

A city of 45,000, Wittenberg felt surprisingly small and quiet given its towering reputation. Maybe it was naive of me, but I somehow imagined the town would be crawling with throngs of Lutheran and Protestant pilgrims. After all, Wittenberg could be considered the Jerusalem and Vatican for the protestants. I have planned this recent trip around the Protestant Reformation, so it was only natural that I made Wittenberg my first stop. Admittedly, I didn't know much about Luther beyond what I learned in high school history class. As a non-Christian, I was excited to dive in and be a temporary Luther pilgrim for a week.

All Saints’ Church

Once I checked into our hotel near the town center, I made a beeline for All Saints’ Church. Also known as the Castle Church (Schlosskirche), this church started as a chapel for the fourteenth-century Ascanian Duke Rudolf I. The chapel was structurally integrated as part of his castle and was actually Wittenberg’s main church for a few decades. In the late fifteenth century, the new ruler, Fredrick the Wise, the Elector of Saxony, founded a university in Wittenberg and made considerable investment in the town, including rebuilding the town castle and a new palace church. A devoted Christian, Fredrick amassed an impressive collection of 19,000 relics in his brand new church and attracted pilgrims from all over the German-speaking lands.

As one of the seven princes-electors, Frederick was a major player in electing the Holy German Emperor. He was actually the preferred candidate put forward by Pope Leo X in the 1519 imperial election. It showcased just how closely he was aligned with Rome in both religious and political terms. However, he was also a political reformer at heart, pushing for changes at the imperial court. With the blessing of the papal envoy, this splendid church also served as the chapel for the University of Wittenberg. Debates on theological issues among the university students and faculty were commonplace. Among the faculty was Martin Luther, an Augustinian monk, who was increasingly alarmed by the abuse and fraud associated with the sale of plenary indulgences.

The selling of indulgences was entrenched in the Roman church for centuries before the time of Luther, but abuses of indulgences became increasingly acute under the papacy of Leo X. In a bid to raise funds to rebuild Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome, the Pope conspired with the powerful Albert von Brandenburg, who had bought his position as the Archbishop of Mainz, to deploy a network of touts within the Holy Roman Empire to promote the sales. Pope Leo and Albert would take a cut. The most infamous of these touts was Dominican friar Johann Telzel, who famously proclaimed: "As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory springs." His tactics were so notorious that Telzel was banned by Frederick the Wise from selling within his realm.

In 1517, Martin Luther posted a list of ninety-five points outlining his criticism of the corruption and the theological danger of Tetzel’s sermons. Luther believed that repentance could bring grace in the sight of God, not the purchase of indulgences. Unaware of Albert’s involvement from the get-go, Luther drafted a letter to Albert in October 1517 to alert him of the abuse and enclosed his ninety-five theses. Luther was worried that Tetzel’s action would bring shame to Albert’s reputation. The thesis was intended to serve as an appendix to explain his positions to Albert. Soon afterward, Luther had the Ninety-five Theses printed by the university press and nailed them on the church doors across Wittenberg, as was customary for academic Disputation at that time.

Luther’s intent in posting the Ninety-five Theses was to jump-start an academic debate among the scholars and clergy, not a public declaration of a political nature. According to the written account of Luther’s colleague, Philip Melanchthon, the thesis was posted on the door of All Saints’ Church on the eve of All Saints’ Day, which is the most important holiday for veneration of relics within the church. While many scholars have brought into question this account, the legend of Luther nailing his thesis to the door of All Saints’ Church in defiance of the church has entered the public imagination over the centuries. This church door inadvertently became the most important “relic” of the Protestant Reformation.

Much to Brian’s disappointment, the original wooden church door, along with much of the church, was destroyed by a fire during the Siege of Wittenberg in 1700. Numerous priceless arts and relics were also lost. However, the profiled stone jambs are the original. The church and the famous door were soon reconstructed. Based on the architectural sketch from 1509, the present church appears to be a faithful reconstruction of the one from Luther’s time on the exterior. In 1858, King Frederick William IV commissioned commemorative bronze doors to be mounted at the original portal to commemorate the 375th anniversary of Luther's birth. These doors bear the inscription of the Ninety-five Thesis. The tympanum above the door depicts Luther and Melanchthon kneeling by the cross, and the medieval skyline of Wittenberg in the background.

Although the famous Thesis doors are accessible to the public at all hours, the church interiors are only visited through the castle, which charges a €3 preservation fee per person. A small exhibit included in the admission provides a concise overview of the Ninety-five Thesis within the broader historical context of Europe. It was actually the first time I had read the English translation of the thesis, and I could attest to just how plain-spoken the texts were. The first section examines the nature of purgatory and addresses how the fate of the deceased could not possibly be interjected through the purchase of indulgences by the living. As the thesis progressed, the texts became sharper and more sarcastic in tone. Like his letter to Albert of Mainz, Luther speculated in his thesis that the Pope must not be aware of the behaviors of the indulgence preachers.

Among all the artifacts on exhibit, our favorite was actually a tapestry of the “Luther Rose” by Queen Margarethe II of Denmark. Luther Rose is the coat of arms of Luther and has since become the symbol of Lutheranism. It was allegedly inspired by the stained glass window at the Augustinian Monastery in Erfurt. As the supreme head of the Evangelical-Lutheran Church in Denmark, the queen came to Wittenberg to pay tribute to Martin Luther in 2016, just ahead of the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation, to oversee the reopening of the restored All Saints’ Church. She is a renowned embroiderer and had said that she personally designed and embroidered this particular altar frontal cloth herself. Brian and I remember visiting the Christiansborg Palace in Copenhagen years ago and being in awe of the Queen’s Tapestry. Encountering her works in Wittenberg felt like seeing an old friend.

After descending a steep staircase, we arrived at the nave of the church. Despite knowing they are not the original, I was impressed by the late Gothic nave with fanciful rib vaults, nevertheless. Richly decorated by Lutheran standards, the church is adorned with life-sized statues of prominent figures from the Reformation, such as Johannes Bugenhagen and Justus Jonas. Most importantly, this is also the resting place of the three key figures: Martin Luther, Philip Melanchthon, and Frederick the Wise.

Fredrick the Wise passed away in 1525 and is buried near the central altar. A lifelong Catholic, he always protected Luther and his followers during his reign, even after Luther’s excommunication by the Pope and the imperial ban from preaching by the Roman Emperor Charles V. Allegedly, he even converted to Lutheranism on his deathbed. After Luther’s passing in Eisleben in 1546, he was buried under the pulpit here. The simple grave was unassuming, which was quite fitting for a reformer championing against extravagance and sainthood. Melanchthon was later buried opposite his friend at the other side of the nave.

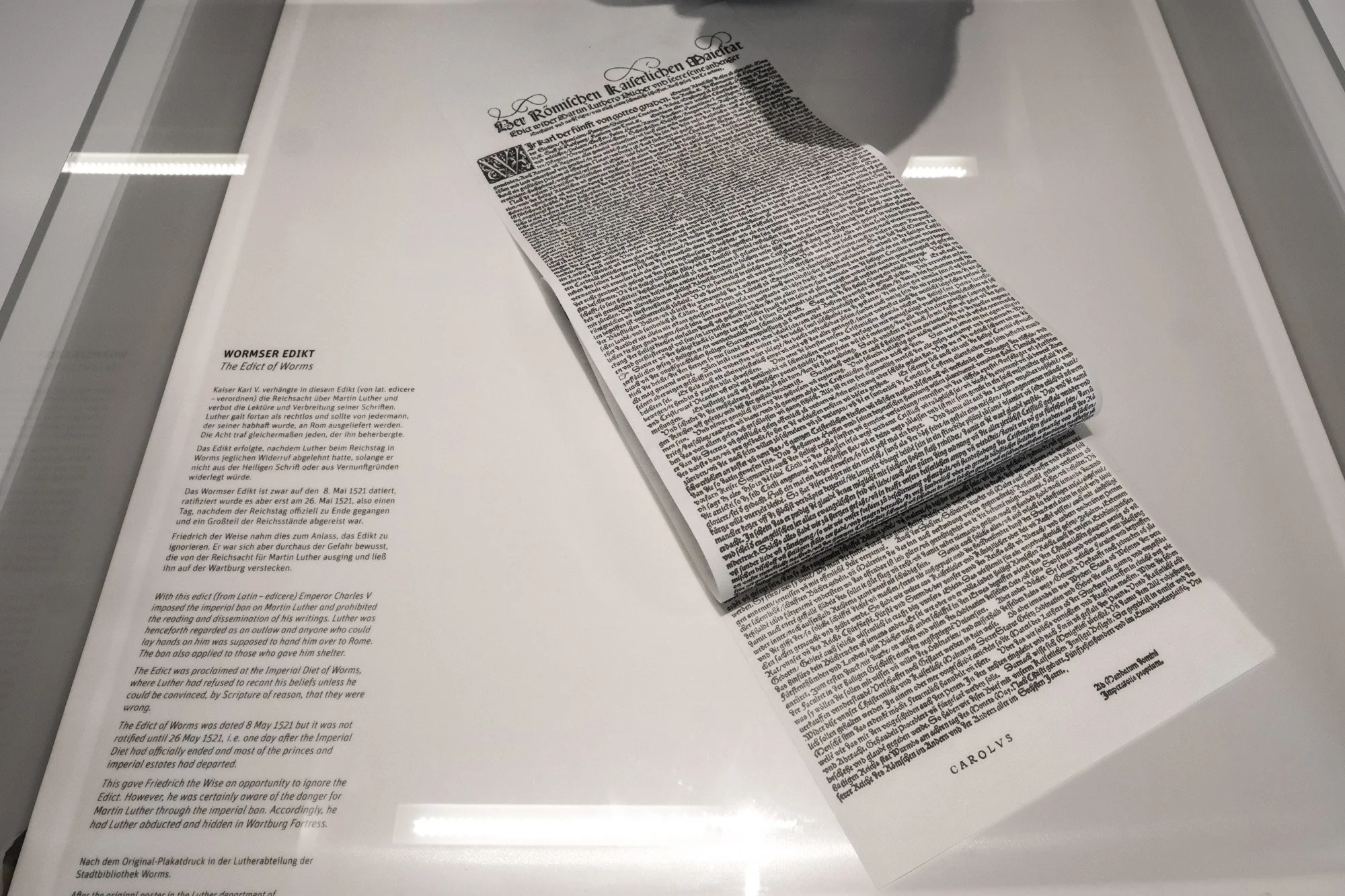

Personally, I was somewhat surprised that no flowers or other tributes were placed on his grave during our visit. Merely a year after Luther’s death, Wittenberg fell and was ceded to the imperial forces of Charles V, who issued the Edict of Worms against Luther two decades earlier. The emperor reported visiting the church and ordered his troops not to disturb the grave of his heretic adversary. Allegedly, the emperor proclaimed, "He has met his judge. I only wage war with the living and not with the dead."

Town and Parish Church of St. Mary's

The next Reformation site is only a short distance away from All Saints’ Church. Completed in 1283, the Town and Parish Church of St. Mary's (Stadtkirche Wittenberg) is the oldest building in the city, and where Martin Luther preached regularly. This church marked the first of many for Lutherans, including the first Mass spoken in German, as well as the first time wine and the sacrament were distributed among the congregation. As such, this is often regarded as the “mother church” of the Reformation. Given Luther’s positions on saints and relics, as well as the importance of spoken words, Lutherans regard this as the most important pilgrimage site in Wittenberg.

Interestingly, Martin Luther preached here as early as 1512, five years before the publication of the Ninety-Five Thesis. The first Protestant service was held here by Justus Jonas the Elder and Andreas Bodenstein for Christmas mass in 1521. Around the same time, an inoclastic campaign began in Wittenberg under the direction of Thomas Müntzer and Andreas Karlstadt. The vast majority of the church’s original decorations were stripped off, and the interior was whitewashed. The cleansing of icons and relics caused civil unrest in Wittenberg, so much so that Luther had to intervene while in hiding as Junker Jörg in Eisenach.

The anarchy in Wittenberg actually drew Luther out from hiding. Contrary to John Calvin and his followers, Luther did not actually advocate for the wholesale removal of Christian icons and arts. He delivered a series of sermons, known as Invokavit sermons.,to clarify his positions on incoclast. He did not fundamentally object to the spiritual objectives; he rejected the spirit and tactic in which they were carried out. He did not wish to replace the irrational worship of icons with man-made laws that prohibit any religious arts. The issue at hand was the veneration of icons and relics; there is no biblical basis that prohibits the creation of religious images.

Speaking of the arts, the most notable object inside the church is the Wittenberg Cranach Altarpiece. Also known as the Reformation Altarpiece, the triptych was created shortly after Luther’s passing and is considered the best contemporary representation of the key tenets of the Protestant Reformation. This beautiful altarpiece was a masterpiece of Renaissance religious art by Lucas Cranach the Elder and his son, Lucas Cranach the Younger. The duo was the court painters to the Electors of Saxony and were close friends with Luther. They were instrumental in spreading Luther’s ideas and popularizing the images of Luther and other prominent figures of the Reformation.

The front panels depict three sacraments Luther deemed to have a biblical basis: Baptism, Eucharist, and Absolution. Luther and his Wittenberg contemporaries are painted into the scene. On the left panel is Melanchthon baptizing a baby, and on the right panel is Bugenhagen, Luther’s pastor, absolving the sins of a man while holding the keys of Saint Peter’s, the traditional papal symbol. Also making an appearance in the altarpiece is Katharina von Bora, a former nun who married Luther in 1525 right at this altar. Their marriage was scandalous at the time, but it set an important precedent for Protestant clerical marriage.

Aside from other oil paintings hanging near the altar, the other important feature inside the church is the impressive organ. Although the present organ is not original to Luther’s time, it nevertheless reminds us of the importance of music in Lutheran worship. Luther took music lessons during his childhood stay in Eisenach and was quite capable of composing liturgy. He personally wrote thirty-six hymns on German texts, many of which survived and are still used in Lutheran liturgy. While Calvinists regarded music as an unnecessary distraction from worship, Lutherans recognize the power of singing in community building and have developed a long tradition of choral music. This tradition has left a lasting legacy in the works of great composers, such as Johann Sebastian Bach and Heinrich Schütz.

Before leaving the church, visitors should look up at the corner of the building's exterior to see a sculpture of Judensau. Translated as Jew’s pig, Judensau is a derogatory sculpture depicting Jews sucking on the teats of the hog and a rabbi examining its ass. Because pigs are considered unclean animals in Judaism, the sculpture was meant as a didactic message to warn citizens of Christian’s superiority over Jews in medieval times. The fact that it was mounted in a prominent location on the exterior was also meant to intimidate Wittenberg’s Jewish population. While Martin Luther was sympathetic about the plights of the Jews in his younger years, He gradually became increasingly anti-semitic. By the 1520s, he wrote extensively about the dangers of Judaism and the resentment toward their unwillingness to convert. Toward the end of his life, his view became increasingly radicalized. He published a 1543 treatise, On the Jews and Their Lies, in which he called for the burning of synagogues, the burning of Jewish texts, religious segregation, and other atrocities.

The presence of Judensau in the mother church of Lutheranism is undoubtedly problematic. Luther actually referred to this particular sculpture in many of his tirades against the Jews. In 2020, a Jewish man sued and demanded the sculpture be removed on its anti-Semitic grounds. It sparked a heated and ongoing debate on how to address historical monuments with problematic histories or messages. The court ultimately sided with the church in recognizing its values as a historical artifact of medieval antisemitism. The judge acknowledged the presence of a Holocaust memorial plaque nearby, which provided the historical context. By removing the sculpture, it might inadvertently erase part of history that is pertinent to today’s society.

Lutherhaus & Melanchthonhaus

For many visitors, the most worthwhile and popular Luther site is actually the Lutherhaus, located on the opposite end of town. While Luther had lived in many different cities throughout his life, this was his primary residence for much of his eventful life. When we first set our sights on Lutherhaus, Brian immediately joked that Luther obviously lived like the Pope! Lutherhaus was initially an Augustinian monastery attached to the University of Wittenberg. It was referred to as the Black Monastery, named after the black robes worn by the Augustinian order. Luther resided here as a monk during his time as a student and professor until he was forced into exile at Wartburg Castle in 1921.

In the chaos of the German Peasants' War in the early 1520s, the monastery and the university were abandoned. When Luther returned to Wittenberg in 1524, John the Steadfast, Elector of Saxony, gifted him the empty monastery. The house was gradually renovated and expanded, eventually becoming a massive home for his growing family. As a prominent figure in the Reformation, Luther constantly received important visitors and students at his house. It was a writing workshop and teaching center as much as a home. By all accounts, Katharina von Bora was an effective manager of the bustling households and directed many construction projects. One notable feature associated with her is Katharinenportal, an elaborately carved Gothic portal that Luther presented to her as a birthday present.

Not all of the grand architecture features we see today at Lutherhaus are original to Luther’s time. Luther’s heir sold the house in 1564 and subsequently converted it into a boarding school, undergoing numerous modifications. Although the house came out largely unscathed during the 1760 siege, it gradually fell into disuse as a military hospital and school for the poor. Today’s Lutherhaus is primarily the result of mid-19th-century restoration work. Although the majority of rooms were relatively modern recreations, Luther’s study and its furniture were said to be the original.

Unfortunately, the historic section of Lutherhaus was closed for extensive renovation until January 2027. Most of the historical artifacts were reassembled into a temporary exhibition called Literally Luther: Facets of a Reformer at the nearby modern annex. The state-of-the-art exhibit offers a comprehensive survey of Luther’s life and his profound impact on world history. Many artifacts on display have an intimate connection with Luther, including the beautiful gold wedding ring he gave to his wife, Katharina. The ring was on loan from the City History Museum of Leipzig for this exhibition. The ring was presumed lost in WWII but was recovered by chance in 1968.

The exhibition does a great job of tracing Luther's life. On display were Luther’s habits as an Augustinian monk and the first complete German Bible edition he published in Wittenberg. Also on display were items of a more intimate nature, including the wooden toy the couple made for their children. Music and beer also seemed to play a big part in his family life. They were discovered during a previous renovation at his parents’ house in Mansfeld. The focus on domestic life is one of the least talked about aspects of Martin Luther. By all accounts, he was a loving husband and father. As a public figure, his family was well-versed in intellectual discussions and spirited debates.

Martin Luther’s success was the result of a confluence of various historical events. One could imagine that Luther might have suffered the same fate as previous reformers, such as the Cathars, Jan Hus, or Girolamo Savonarola. Besides the patronage of Frederick the Great and the favorable political climate within the Holy Roman Empire, the Reformation would not have happened without the advent of print media. Just a few generations behind Johannes Gutenberg, Luther and his followers weaponized the press to disseminate their ideas in texts and images. Luther was an indisputable social media star of his time.

Since we don’t know German, we were naturally drawn to the sensationalist imagery printed during this period. Some of them were absolutely savage, depicting the Catholic clergy as anti-Christian deviants. My personal favorites were the anti-papal satirical medal that shows images of the Pope wearing a papal tiara. But when we spun it 180 degrees, the same image became a devil with protruding horns. The ingenuity of propaganda back then was quite inspiring. It was fascinating that not one single individual could single-handedly effect a revolution like the Protestant Reformation.

The final section of this exhibit highlights the global reach of Lutheranism today. During the East German days, Martin Luther was elevated as a figure of German nationalism. Curiously, less than half of Christians in Germany were Protestant, with Lutherans accounting for less than a quarter of the country’s total population. Within Europe, Lutheranism is most dominant in the Nordic countries, where the state church was part of the Lutheran faith. Outside of Germany, countries with the most Lutheran congregants are Ethiopia, Tanzania, Sweden, Indonesia, and India. One of the newest items in the exhibit was a painting of Martin Luther dressed in hakchangui, the traditional Korean garment worn by Confucian scholars. It was a gift from Korean artist Cho Yong-jin in 2017, showcasing Luther’s legacy in the Protestant faith in Korea.

As a consolation for Lutherhaus’s closure, visitors could purchase a combo ticket with Melanchthonhaus for only €2 more. Melanchthonhaus was the residence of Philip Melanchthon, a close associate of Luther and a fellow professor at the University of Wittenberg. Although Luther is the spiritual leader of the Reformation, it was Melanchthon who helped distill Luther’s teaching into a comprehensive theology. Luther’s bombastic rhetoric does not always translate well into systematic teachings. Compared to Luther, Melanchthon was more temperamentally suited for an academic environment. He often defended Luther in public debates and was particularly prolific in synthesizing the ideas of the Reformation.

Melanchthon’s academic background enabled him to write concisely and clearly. His most important work was the Augsburg Confession. Presented at the Diet of Augsburg at the request of the Holy Roman Emperor in 1530, the document was the confession of faith of the Lutheran Church. The pair worked closely together, but it is fair to say that Luther’s legacy would have been far less impactful without Melanchthon’s conscientiousness and moderation. His aversion to conflicts also meant he was keen to exchange ideas with other noted reformers, such as John Calvin and Heinrich Bullinger.

Outside of religious reform, Melanchthon was also a noted education reformer. He was a strong advocate of teaching Greek and Latin to young students as a vital path for personal growth. He developed a curriculum for numerous reformed schools based on Christian Humanism and wrote extensively on educational matters. Like Luther, he was concerned with the populist and anti-intellectual strains within Protestantism. Education is not merely to understand the scripture better, but also for the betterment of society. Upon his death, he was bestowed the distinction of the Teacher of Germany (Praeceptor Gennaniae).

Melanchthonhaus was built in 1536 by John Frederick I, Elector of Saxony, and gifted to Melanchthon as an incentive to retain him as the university professor. Sporting an impressive Renaissance-style gable facade, it is one of the oldest and most beautiful private residences in Wittenberg. Unlike Lutherhaus, his residence was largley untouched over the centuries and continued to serve as a faculty residence for the university. Unsurprisingly, most period furnishings on display today were not original to the house. However, fragments of original wall paintings, including coats of arms of visiting scholars, were discovered during the late 19th-century renovation.

Besides showcasing Melanchthon’s works in the Reformation and Christian Humanism, the museum also houses numerous works by Lucas Cranach the Elder, including portraits of Melanchthon. Like Luther, his images and the account of his life (and death) were widely circulated in the German-speaking lands and Protestant realms. Melanchthon had a distinct/deformed facial feature and stature, making him instantly recognizable among the pantheon of Reformation leaders.

Historic Center of Wittenberg

All the blockbuster Luther sites aside, the historic center of Wittenberg is a worthy stop in its own right. Thanks to Wittenberg’s stature as the cradle of the Protestant Reformation, the town was largely spared by aerial bombardment during World War II. Organized by a series of three gently curved and parallel streets, the city feels well-organized but still retains its historic ambiance. One of the most amazing pieces of historical facts I learned during our visit was that Luther and his principal patron, Frederick the Wise, had actually never met in person. That is almost inconceivable given Luther’s fame and how compact Wittenberg was and still is.

As in Luther’s time, Marktplatz, the Market Square, dominates the town center, and it is still the center of activities. Standing in front of the town hall are life-size statues of Luther and Melanchthon. The Luther Monument in the middle of the square, dated to 1821, was the first statue to memorialize Martin Luther. The statue was a reaction to the occupying Napoleonic forces at Wittenberg. The citizens of Eisleben and Mansfeld commissioned it to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the posting of the Ninety-Five Theses. It is not only the oldest memorial to Luther but also the first free-standing statue honoring a commoner in Germany. It symbolizes a shift to the interpretation of Luther as a national figure in modern Germany. He has been co-opted by generations of German leaders, from Frederick William III of Prussia, Adolf Hitler, to Erich Honecker.

Visitors to Wittenberg could be hard-pressed to escape the story of the Reformation. Fair or not, it was also as if the city’s entire existence rested upon Martin Luther. Hanging above many buildings’ doorways are plaques dedicated to various protestant figures who used to live in the building. Just off the main street are a series of charming medieval courtyards. The most famous among them would be Cranachhof, which was home to Cranach's painting and printing workshop. The family was one of the most successful Renaissance artist workshops in Germany and is intricately linked to the story of the Reformation. While we missed out on the exhibition at the workshop, one could argue that it is just as important a Luther site as Lutherhaus.

The last historical site that is worth mentioning, in my opinion, would be the Luther Oak. Located a few hundred feet southeast of Lutherhaus, the massive oak tree was planted in 1883 to mark the spot where Martin Luther burned his copy of the papal bull threatening him with excommunication. Also thrown into the bonfire were books of church doctrine that Luther deemed to have no biblical basis. As inspirational as Luther’s actions may seem, let’s not forget that both sides of the debate committed book burning, which could be regarded as libricide by our contemporary standards. Ironically, the original oak tree was inadvertently chopped down by the French troops in 1813 due to a shortage of firewood.

For a city that is intricately linked with the Reformation, the majority of the population here is irreligious nowadays due to decades of state atheism under East German rule. According to a 2018 survey, only one in two residents of Saxon-Anhalt identified themselves as Christian, the lowest among all the German states. I can’t help but wonder if it is the reason why Wittenberg feels more like a historical museum than the Vatican. For many opponents and some modern proponents of Luther, the gradual shift toward irreligious Humanism is actually a natural evolution of the Reformation. On the other hand, I am certain that Luther would be agast by the pluralist ideals of our contemporary society.