The Memories of Buchenwald

Although our recent trip to Germany centers around the Luther Trail and the Bauhaus, our visit to the Buchenwald concentration camp turned out to be the most memorable and moving experience. I visited the Auschwitz concentration camp in Poland more than a decade ago, and that was a disconcerting and moving experience. Since then, I have become more worldly and now have a deeper understanding of the history of the Holocaust. With right-wing populism and anti-semitism now on the rise in the West, a visit to a concentration camp seems particularly timely at this moment. I was also interested to see how the German government managed the legacy of a concentration camp within the German “homeland.”

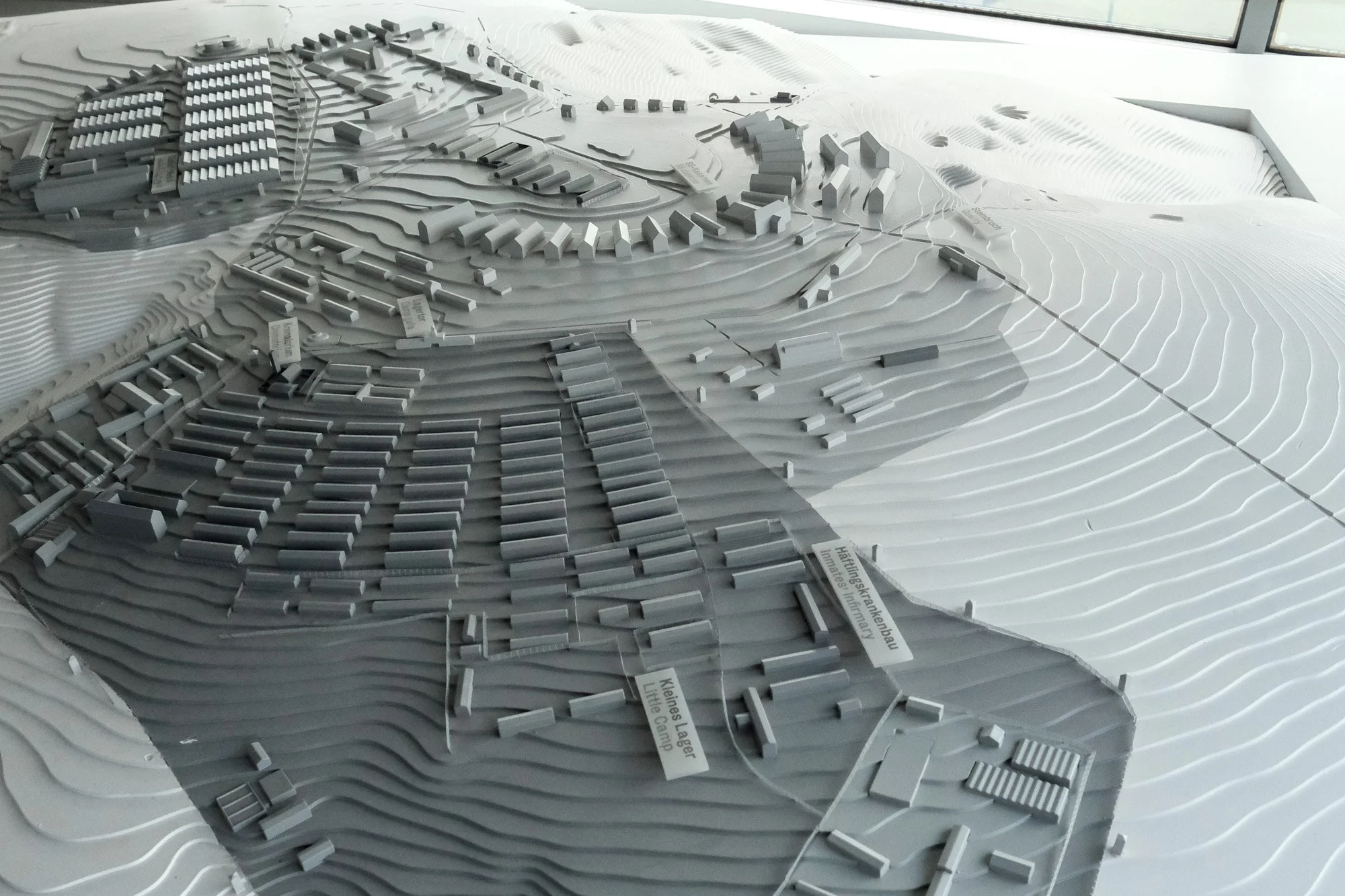

Located just five miles outside of the city of Weimar, Buchenwald is far from the most notorious concentration camp in the Nazi Reich. However, it is the largest camp within the territory of the “Old Reich.” It functions primarily as a labor camp in the system, often taking in inmates transferred from other camps like Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen. Most inmates were subjected to forced labor by working in Weimar’s armament factories. Even though this was not an extermination camp, the prisoners were not treated any better than elsewhere in the system. According to historians, approximately 56,000 inmates perished at the camp.

The camp was founded in 1937 and was supposedly to be named after the nearby Ettersberg Hill, which has a close historical connection to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Weimar Classicism. Ironically, Weimar’s cultural elites objected not to the camp's existence but to its association with the German Enlightenment. They ultimately named the camp Buchenwald, after the nearby beech forest. This camp was actually a consolidation of smaller concentration camps in the region. The camps’ proximity to Weimar was deliberate, intended to maximize the economic output of inmates in the industrial sector.

After picking up the handy audio guide at the visitors’ center, the tour started at the platform of Buchenwald Train Station. For anyone who had been to Auschwitz, the railway platform holds a particularly sinister significance as the selection platform that determines whether one would be sent directly to the gas chamber. Buchenwald Station, on the other hand, functioned purely as a transport hub, carrying both inmates and local workers from central Weimar. Directed by Heinrich Himmler, the railway line was constructed by the inmates. The inmates were treated brutally so that the six-mile rail line could be completed in record time.

From the platform, it was only a few minutes’ walk to the camp’s entrance gate. The passage way is named Caracho Way, named after the Russian word meaning “good”. With the help of their guard dogs, the SS guards would yell Caracho! to herd inmates to the camp gate, forcing them to run en masse. The intimidating tactic was reportedly one of the most vivid memories for many survivors of Buchenwald. At the start of the passageway, there used to be a wood carving depicting running inmates. It was the work of Bruno Apitz, a German communist who was imprisoned here. The sculpture survived and can be found in the camp's permanent exhibition today.

Lining the Caracho Ways are two rows of single-story structures that serve as the guards' administrative offices. The famous commandant of Buchenwald was Karl-Otto Koch, one of the most notorious SS commanders in history. He and his staff documented their crime in the neatly kept photo albums. Koch was later demoted and prosecuted for various crimes by the Nazi regime and was executed by firing squad a few weeks before Buchenwald’s liberation. He was convicted of embezzlement, mismanagement, and, most ironically, the murder of three inmates. The murder charge was brought up because those inmates were killed to prevent them from testifying for the embezzlement charges.

Curiously, Koch’s notoriety was actually eclipsed by his wife, Isle. She was known for her particular cruelty. She is most famous for allegedly selecting Jewish prisoners to have their skin flayed and made lampshades out of them; the tales of her sadism took up a life of their own. During her trial for war crimes by the American occupation forces, there was little direct evidence linking her to the various human artifacts found at Buchenwald. Nevertheless, she was found guilty and avoided the death penalty only because of her pregnancy at the time of the trial. Although she was not the only woman convicted of Nazi war crimes, no one, except for Irma Grese, achieved the same level of infamy.

Just like Auschwitz, Buchenwald’s most emblematic monument is the Gate Building. It was the central watchtower and the only point of entry into the camp. All announcements were made from the loudspeakers on the upper level. To the left of the main entrance is a series of detention chambers where interrogations and torture took place. Each cell bears the name of victims murdered here. Among them were an Austrian Catholic priest, a German politician, and a Polish farmer; this demonstrates the varied backgrounds of the victims of Buchenwald.

Having been to Auschwitz-Birkenau, I can’t help comparing the two camps. Buchenwald has its own version of Arbeit macht frei (Work makes you free). The phrase "Jedem das Seine" (To Each His Own) originated in Roman times as a term for justice. The Nazis co-opted the phrase to condemn those who did not conform to the ideals set out by Nationalist Socialism. The phrase is integrated into the main gate and is visible from the roll call square, where inmates would gather daily. The lettering was painted in blood red and repainted every year. Like Arbeit macht frei, this phrase seems innocent in its plain text, but carries so much historical baggage. The phrase was used in commercial advertisements in Germany from time to time, and each time it was marred by controversy.

Design enthusiasts might notice that the phrase was written in a Bauhaus-style font. Franz Ehrlich, a Bauhaus student, designed it, and he was imprisoned here for his affiliation with the Communist Party. Because of his talent as an architect, he was drafted to design the infamous entry gate, the commandant’s office, and various furniture for the officers. In an odd twist of fate, Ehrlich was eventually released by the SS and worked under the architect/planner of Buchenwald, Wolfgang Grosch, before transferring to the headquarters of the SS Construction Department. Needless to say, his legacy was complex and remains a subject of considerable debate. However, some inmates later testified that Ehrlich secretly aided the resistance movement at Buchenwald. We actually came across an exhibition at Weimar’s Bauhaus Museum dedicated to the complicated life of Ehrlich.

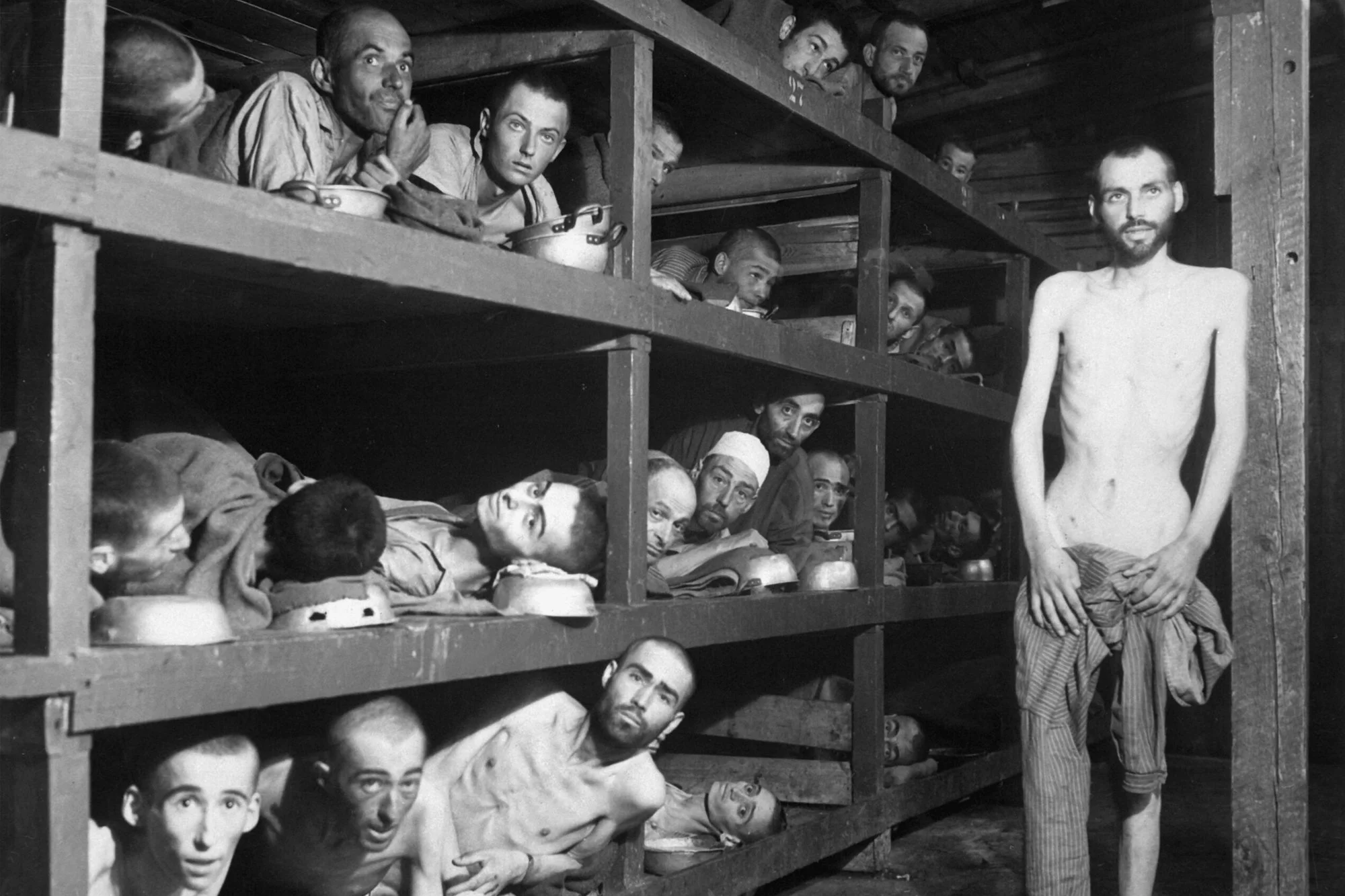

As at Birkenau, most of the original barracks were demolished during the GDR. That said, the scale of the camp was nevertheless stunning. It was all too easy to underestimate how many inmates were imprisoned here. More than a quarter of a million individuals passed through the gate here. Not surprisingly, the camp soon became overcrowded from the get-go and housed more than 112,000 at its peak. Inmates were forced to share beds with appalling hygienic conditions. Twice a day, inmates were herded to the roll call square to endure hours-long roll call, no matter the weather and temperature. It was a sadistic way for the Nazis to “weed out” the physically weak.

With fifty barracks, the camp was subdivided into different zones to segregate inmates into groups. Among the classifications included were the Jews, Soviet prisoners of war, German political dissidents, Roma, and Sinti. There are memorials dedicated to each group dotted across the camp. The most evocative one is dedicated to the murdered Roma and Sinti. Because “gypsies” were one of the undesirable groups under National Socialism, they were subjected to racial research. This memorial in Block 14 was the first of its kind in Germany and consists of 100 black basalt steles and a mound of black gravel. The rustic, diminutive appearance speaks to the sorrow of these often-forgotten victims.

Of all the sub-camps at Buchenwald, the most notorious would be the aptly named Little Camp. Situated on the northern edge of the camp, this section was originally built as a horse stable and functioned as a quarantine area, and was notorious for its unsanitary conditions, even by concentration camp standards. The mortality rate was particularly high. The most famous inmate imprisoned here was Elie Wiesel, the Nobel laureate in literature and perhaps the most famous Holocaust survivor. He authored more than fifty books, the most famous being Night and Day, based on his memories in Auschwitz and Buchenwald. His books were actually the most memorable read in my high school English class. Serendipitously, he was photographed in the barracks five days after the camp’s liberation by American troops. When President Barack Obama visited Buchenwald with Chancellor Angela Merkel in 2009, Wiesel served as their guide, providing a firsthand account of his experiences.

At the southern end of the Little Camp is a special barracks, Block 66. As the number of juvenile inmates increased at Buchenwald, many inmates made a concerted effort to set up a special children's section to allow them a better chance of survival. Most children imprisoned here were orphaned Jews from Poland and Hungary. Despite the harsh conditions, many sympathetic adult inmates worked hard to procure additional food and security for these kids. Shockingly, over a third of inmates at Buchenwald were under twenty years old. The absence of humanity is really thought-provoking and a warning to us all.

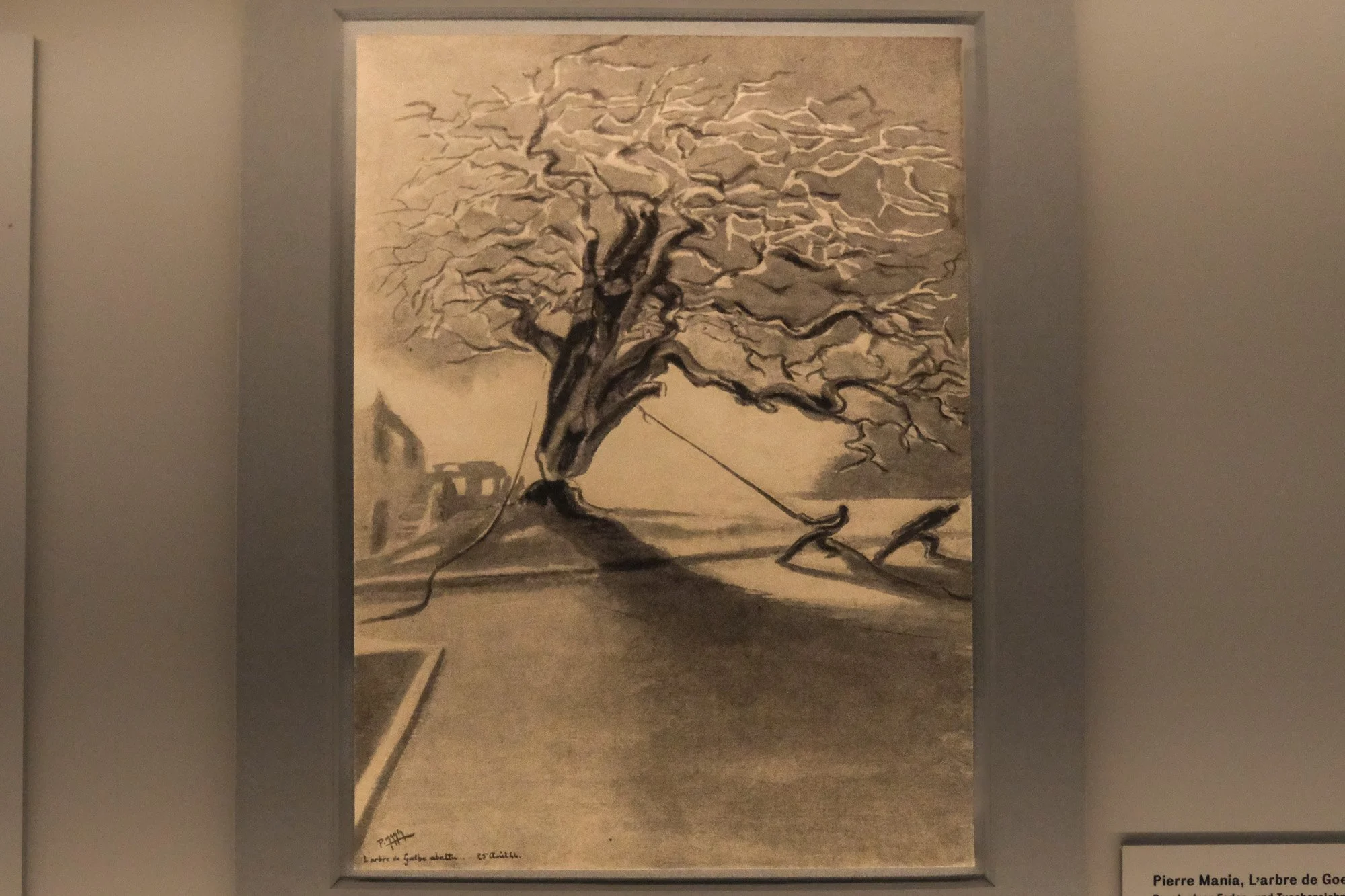

To me, the most underappreciated monument in Buchenwald is a tree stump on the eastern side of the camp. Known as the Goethe Oak, the tree stump played a pivotal role in Buchenwald's history. As noted earlier, the campsite was formerly known to the people of Weimar as Ettersberg Hill, a name revered in German culture. Allegedly, Goethe composed some of his most famous works under this giant oak tree. When the Nazis cleared the forest, they left this lone oak standing out of respect for one of the most famous Germans. For SS guards, the Goethe Oak symbolized Germany’s cultural superiority, and they saw themselves as the legitimate successors of Weimar Classicism.

Cynically, the Nazis hanged many prisoners from the oak’s branches. As the camp developed, the Goethe Oak’s condition deteriorated due to disturbance from building activities. By 1944, the tree had lost all its leaves. Many inmates considered it a symbolic death of the Enlightenment or the impending end to the Nazi tyranny. The oak met its end when it was engulfed during an American air raid, and no inmate attempted to save it. When the oak was eventually cut down by the guards, many inmates gathered scraps as memorabilia, many of which was ehibited in the camp. German communist Bruno Apitz famously carved an image of a dying inmate in a piece of Goethe Oak during his imprisonment here.

An unexpected highlight of the visit to Buchenwald was the massive storage depot. It was the largest and one of the best-preserved in the camp. Since 1985, the building has been converted into an exhibition space. The state-of-the-art multi-media exhibits provide an excellent overview of the camp's history through the building’s three floors. Through hundreds of artifacts and personal testimonies, the exhibit offers a glimpse into the lives of inmates. Most interestingly, the exhibit highlights Weimar's culpability in the operations of Buchenwald. After the liberation, most citizens of Weimar denied any knowledge of the concentration camp in their own backyard. The American commander, General George Patton, actually forced one thousand of the Weimar residents to confront the atrocities.

When the residents pleaded ignorance, liberated inmates confronted them. The tacit complicity of the German population is always an uncomfortable topic to address, but the museum was not shy about addressing it. As a labor camp, inmates were often transported to nearby factories. They often worked side by side with the local population on the factory floor. On display in the museums are replicas of Friedrich Schiller’s furniture, created by the prisoners. They were commissioned as temporary war-time replacement while the originals were locked away for safekeeping. It was such a great irony that these “racially inferior” prisoners were forced to glorify the memory of Weimar Classicism.

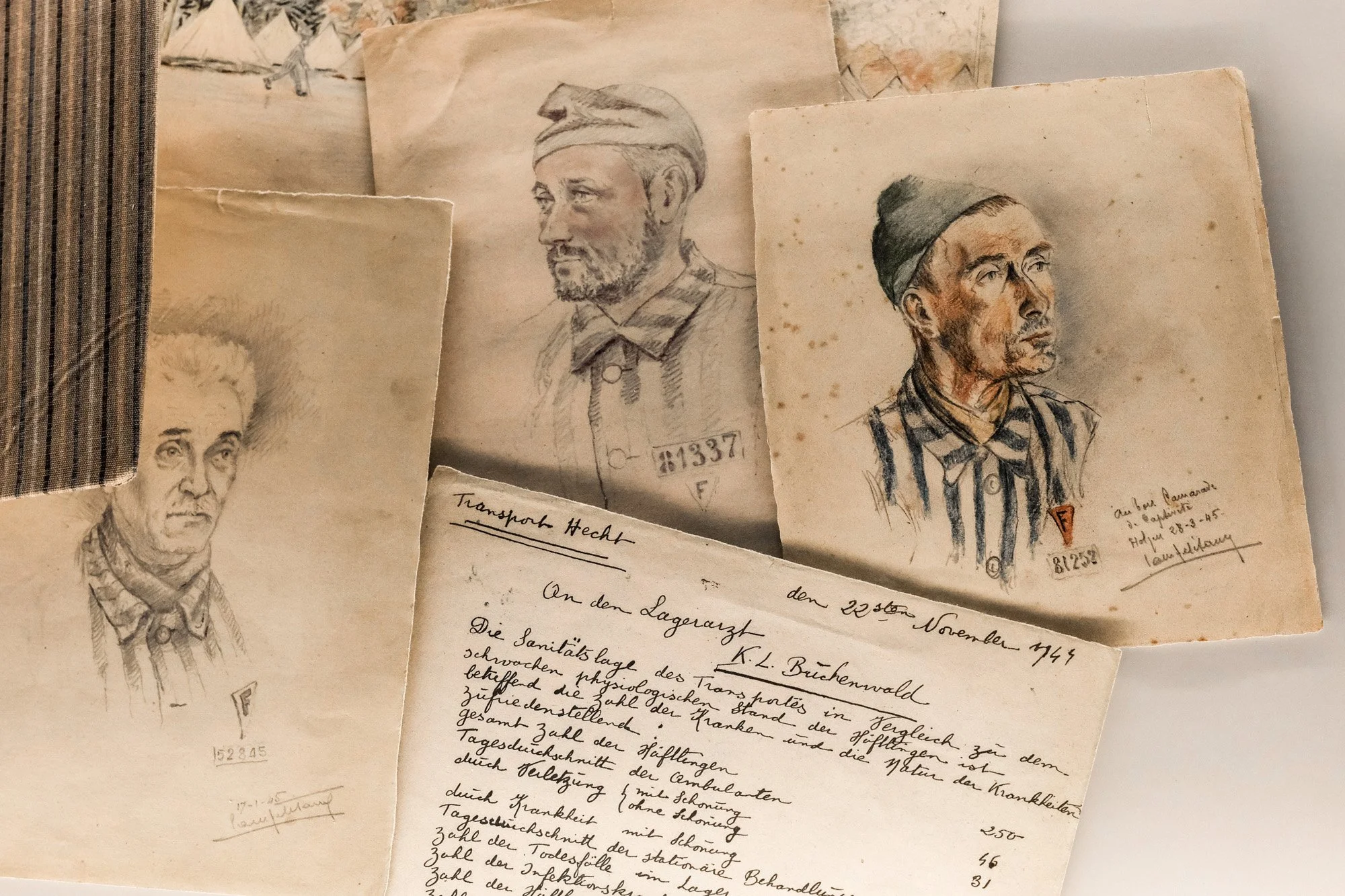

Compared to my visit to Auschwitz fifteen years ago, the exhibition at Buchenwald was absolutely top-notch. It was honestly difficult to provide a succinct overview. Instead, I would like to highlight a few of the most extraordinary artifacts on display. My favorite was a series of Camille Delétang, a French inmate who managed to gather supplies inside Buchenwald to sketch portraits of fellow inmates. In April 1945, Delétang was evacuated from the camp by train as Allied forces approached. Their convey were ambushed and caught fire. In the chaos of escape, he lost his prized collection of sketches. They were presumably lost until miraculous rediscovery in 2012. The reemergence of these portraits offers an intimate look at inmates’ humanity. I could only imagine what an emotional reception would be from the victim’s descendants.

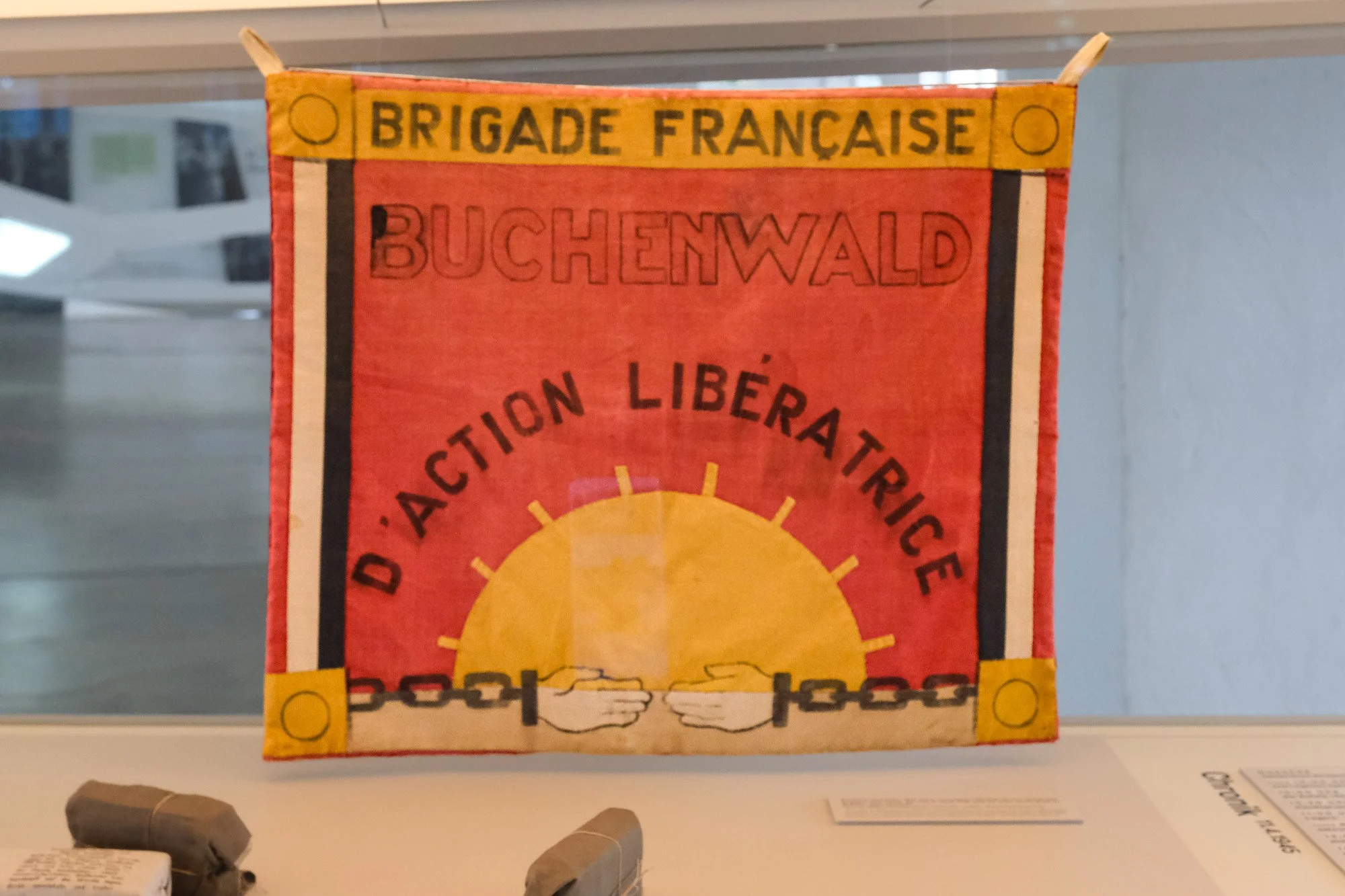

Throughout the camp’s operation, there had always been an underground resistance movement. Known as the International Buchenwald Committee, the clandestine group was founded by German political prisoners and quickly expanded to include members of other nationalities. The committee became organized with hidden weaponry by 1945. When the SS officers evacuated the camp because of the advance of American troops, the committee organized a successful uprising to overpower the remaining SS guards. The camp was officially liberated by the Americans on April 11, 1945. The clock at the gatehouse is now permanently fixed to a quarter past three, the moment of Americans’ arrival.

One week after the liberation, the political prisoners held a memorial service for all the victims of Buchenwald and set up a temporary memorial in the form of a wooden obelisk. The committee members took an oath to defeat Nazism and bring those responsible for atrocities to justice. More importantly, the “Buchenwald Oath” aims to create a world free of conflict. Since so many of the political prisoners at Buchenwald were communists, the oath played a significant role in the political narrative of the GDR. Unfortunately, the temporary memorial obelisk was removed, but later reconstructed at the bottom of the hill.

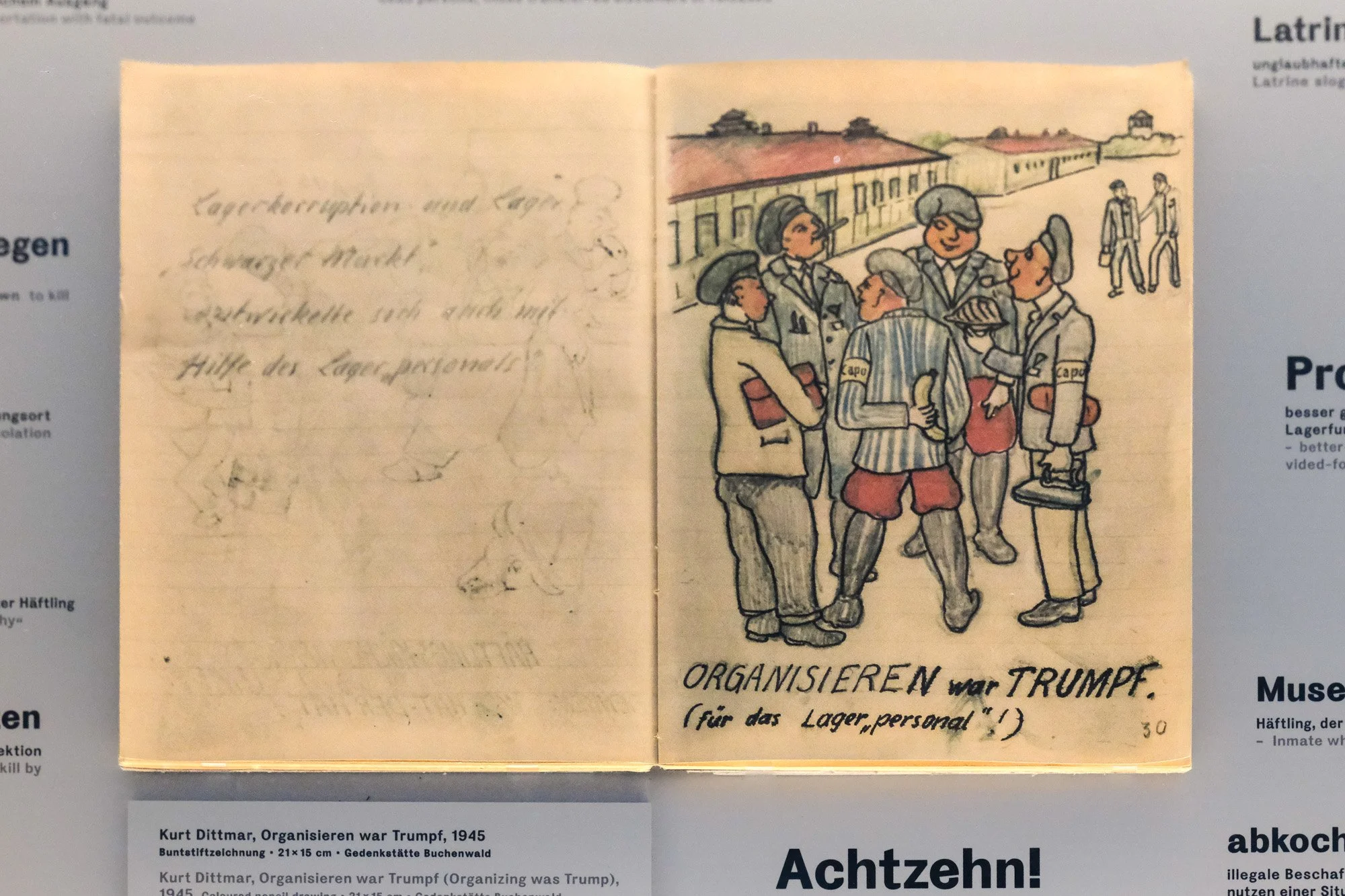

Immediately west of the storage depot are the disinfection chambers. Newly arrived inmates at Buchenwald must stop here first to hand over all their possessions, including all their clothing. Like in Auschwitz, all their hair and body hair were shaved off, and they were forced to walk naked to the storage depot. It was a humiliating experience meant to remove all individuality from them. All the articles are disinfected in a series of concrete chambers, which are preserved to this day. The building was originally slated for demolition along with all the barracks, but was saved at the last minute to become a museum. Nowadays, the building holds a permanent art exhibition: "Means of survival - testimony - work of art - pictorial memory".

This amazing exhibition is dedicated to artworks by former inmates of Buchenwald. The first room includes works done in captivity. I was quite surprised by how many original works, including murals, survived. Even in such dire circumstances, the works' artistic qualities were stunning. With so few photographs taken, the artworks are important testimonies to life in the camp. While most artworks are very dark, as one would expect, many also convey an optimistic tone about humanity. The marquee work is a massive installation called "Reminiscences" by Polish artist Józef Szajna, in memory of 160 of his fellow professors and students at the Academy of Fine Arts in Krákow who were murdered by the Nazi. The work properly captures the erasure of individuality by the Nazis.

Just because Buchenwald was a labor camp, it did not mean the camp lacked the most notorious feature of a concentration camp: the crematorium. The Nazis originally cremated prisoners’ bodies at Weimar’s municipal crematorium, and the camp did not have its own facility until 1940. For some years, Weimar even offered the option to send the ashes to the inmates’ hometown for a fee. Even though there was no gas chamber, inmates were kept in a constant state of starvation. Many were executed at will by firing squad or hanging. During its eight-year operation, as many as 55,000 inmates perished, including many prominent figures.

At the entrance of the crematorium is a room filled with memorial plaques for individual victims. While browsing casually, I came across a plaque for Paul-Émile Janson, the former Prime Minister of Belgium. Arrested by the occupying German troops, he died of hunger and cold on March 3, 1944, at the age of 71. Janson may possibly be the most high-profile politician to die in Buchenwald. It was jarring that even the head of government of a prominent nation could face such an unceremonious end.

As in Auschwitz, the Nazi also used inmates for medical experiments. Attached to the crematorium was a dissection room. This was where the tattooed skin of deceased inmates was removed and turned into everyday objects for Ilse Koch. Many human organs were harvested and sent to major German universities and hospitals for study. Right underneath the cremation furnaces was a chamber that the Gestapo used for execution. Men and women were hanged on wall hooks as part of tortured interrogation. To me, this was probably the most terrifying room in the whole camp.

Even by the standard of a concentration camp crematorium, the most sinister feature of the crematorium complex here is the execution chamber for Soviet prisoners of war. Attached to the crematorium building was a former stable. In 1941, the German High Command issued an order to execute any Soviet political officers captured on the battlefield, which has always been considered a war crime. As the Nazi’s campaign against the Soviet Union ramped up, the number of Soviet POWs exploded. To expedite the killing, the SS fashioned a unique execution facility. Under the guise of medical examinations, the prisoners were instructed to lean against a wall to measure their height. The SS executed the unsuspected prisoners at theneck by pistol through a narrow slit from behind. The medal crates on the floor, which are typical for a stale, make cleanup very efficient.

One of the most unusual features at Buchenwald was the Buchenwald Zoo. Located directly opposite the barbed wire, this miniature zoo was commissioned by Karl-Otto Koch in 1938 and served as a recreational facility for the SS and their families. It housed a small collection of animals, such as deer and brown bears. In sharp contrast with the inmates on the other side of the fence, these animals were extremely well fed and cared for by the SS. All the inmates could easily see these animals from the other side of the fence; it was clearly a psychotic method of denigration of human spirits. A remnant of the original bear enclosure has been preserved and is now a testament to the Nazi cruelty.

Overall, we spent over two hours at the camp and could easily have stayed another hour. For €5, the handy audio guide gave us an excellent overview of a few dozen stops. Alternatively, one could download their audio app. Even though this trip to Germany has been a pilgrimage to all the Martin Luther sites, the visit to Buchenwald was the most impactful and meaningful. Visiting a concentration camp on vacation may seem odd, but it is an absolutely rewarding experience. With populism and fascism on the rise around the world, learning about the Holocaust is more pressing than ever.

The story of Buchenwald extends far beyond the day of liberation. After the war, the worst perpetrators were tried by an American-led tribunal. The Buchenwald Trial led to numerous convictions, but only nine were executed for crimes against humanity. Notably, Isle Koch received a life sentence because of her gender and died by suicide in 1967. Administering justice in the aftermath of mass atrocities was always difficult; many convicted eventually had their sentence reduced. Looking back at the Buchenwald Oath, ensuring world peace seemed like a more feasible objective.

Buchenwald and Weimar became part of the German Democratic Republic (GDR). Backed by the Soviet Union, the government was eager to celebrate the defeat of Nazism by the Communism. Buchenwald inadvertently became a place of potent political significance. Memorials at former concentration camps became one of the pillars of legitimizing the rules of the GDR. In 1958, the government inaugurated a massive memorial complex at the mass grave sites of Buchenwald victims. Located not far from the camp, the memorial is clearly visible from much of Weimar and is the largest memorial of its kind in Europe.

The complex is set up as a one-way loop. The first section is a pathway that is lined with seven massive steles, one for each year of the camp’s existence. Each stele features a sculptural relief and text recounting the camp's history, from its construction to its liberation. The path eventually led to the first mass grave, which was ringed by a circular wall.