Weimar - Birthplace of The Bauhaus

If you have clicked on this blog post, I imagine you might be in the know about the Bauhaus. Aside from the Luther’s Trail, the other scene of this recent trip was to follow the footsteps of the Bauhaus. This short-lived German art school revolutionized and redefined art education and the development of applied arts. As a practicing and licensed architect who focuses on designing modernist buildings, I have long viewed the Bauhaus as the forefather of international modernism. The Bauhaus is one of those terms mythologized by generations of designers, so I was excited to trace the evolution of the Bauhaus from Weimar, Dessau, to Berlin.

The Bauhaus’s six years in Dessau is often considered the golden age of the school. At Dessau, the Bauhaus made a significant pivot from the theoretical to the applied arts, thus making its impact felt more tangible. The chapter in Weimar was often overlooked, especially by architects like myself. I felt a little embarrassed that I did not pay more attention to this part of the Bauhaus in my architectural history class. Since all art movements are the product of their time, there would be no Bauhaus without the interwar Weimar.

Monument to the March Dead

Chronologically speaking, my Bauhaus pilgrimage in Weimar began at the vast Weimar Central Cemetery. While most visitors came to pay their respects at the graves of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Schiller, the monument I was interested in is a relatively little-known landmark on the southern side of the cemetery: the Monument to the March Dead by Walter Gropius. Gropius was the founder of the Bauhaus and a noted architect in his own right. His most notable early work was the Fagus Factory in Lower Saxony. It cemented his reputation as one of Germany’s preeminent modern architects.

To better understand the birth of the Bauhaus, it is helpful to understand the prevailing artistic movements that were in vogue before the rise of the Bauhaus. The most popular movement in Weimar Germany was Expressionism, which focuses on portraying emotional experiences over physical reality. The most iconic Expressionist painting would be The Scream by Edvard Munch. Most historians consider this movement to be a reaction to the horror and social upheavals of World War I. When it comes to architecture, the iconic Expressionist buildings include the Einstein Tower in Potsdam and Bruno Taut’s temporary Glass Pavilion.

In 1920, Walter Gropois and Fred Forbát won a design competition hosted by Weimar’s workers union and the municipal museum to design a monument at the grave site of the seven victims of the Kapp Putsch. The Kapp Putsch was a far-right insurrection/coup attempt against the democratically elected Weimar Republic. Gropius’s design resembles a lightning bolt and is a “symbol of the living spirits.” The monument is said to be the world’s first monument to the dead in abstract and modernist language. The emotive design actually attracted criticism from Theo van Doesburg, the leader of the De Stijl movement.

Soon after the Nazi came to power in Weimar in 1936, the monument was labeled as degenerate art and unceremoniously demolished. It was rebuilt after the war, albeit in a slightly different form. While the monument is far from the design philosophy of the Bauhaus, it embodies the revolutionary spirit of the day and how artists of the age were ready to break the traditional mold. Weimar’s Bauhaus Museum actually adopts the architectural plan of this monument as the cover image for their special exhibition: Bauhaus and Politics. Much to Brian’s befuddlement, the architect within me was just giddy about standing in front of such an architectural icon. I still vividly remember the reading about this monument in Kenneth Frampton’s Modern Architecture: A Critical History in graduate school.

Bauhaus-University Weimar

Five years before Gropius’s monument, a Belgian architect, Henry van de Velde, was forced to resign as director of Weimar’s Grand Ducal Saxon School of Arts and Crafts. He recommended Gropius as a suitable replacement. After prolonged discussion, Gropius was appointed as director of a new art school, which combined fine arts and applied art under one institution. Rather than naming the school as an academy, he names the institution as the State Bauhaus in Weimar, signaling a new approach to art education. The founding coincided with the Weimar National Assembly, which drafted and approved the new constitution for the post-war Weimar Republic. There was a palpable sense of optimism amid the post-war turbulence.

Gropius was a natural evangelist for his visions. He distributed the Bauhaus manifesto and attracted students from all over Germany. The full synthesis of traditional crafts and modern arts was achieved by rethinking art education. The Bauhaus is most famous for the Preliminary Course, which was the foundation study required for all incoming students, regardless of whether the students had prior experience in any particular field. The most influential figure in the development of the preliminary course was Johannes Itten, a Swiss designer and theorist. These courses focused on color theory, materiality, compositions, and spatial theory. Students were encouraged to explore the emotional effects of colors.

With Gropius and Itten, the Bauhaus attracted many leading European artists to teach, such as Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky. As a follower of Mazdaznan, Itten increasingly blended religion, philosophy, and art education. He shaved his head and started to dress in a monk-like habit. His “unorthodox” personality and blending of religion and art education caused increasing unease among the Bauhaus community. As Walter Gropius sought to pivot the school toward applied arts, Itten eventually left the school after three years.

The term Bauhaus is a derivative of the term Bauhuette, a medieval mason’s lodge or the house of builders. From its inception, the sense of community was integral to the foundation of the Bauhaus. Faculty and students would mingle socially, and the school sponsored numerous social events during the semesters. While most people identify Bauhaus with austere modern buildings made of concrete and glass, life at the Bauhaus was anything but austere. Reflecting the progressive social attitude of Weimar Germany, the students at Bauhaus knew how to throw a party. One popular spot for the students is a restaurant called Ilmschlößchen, which was unfortunately closed a few years ago. These parties were most often themed, with students and faculty fashioning their own avant-garde costumes and elaborate stage sets. The most legendary party was the so-called “Metal Party” in 1929, where all the attendees dressed in costumes made of only metals.

The term “Bauhaus ball” became legendary in the architectural community, even to this day. Themed parties are still popular among many architecture schools. When I was in architectural school, the administration put a lot of emphasis on “studio culture”. Just about every school would have its own “architecture studio culture policy.” Architecture school is known for grueling hours and camaraderie. Personally, studio culture equates to a lifestyle that only architecture school could understand. I honestly had no clue how influential the Bauhaus has been on art and design education until very recently. It is perhaps the least talked-about legacy of the Bauhaus.

Just a stone’s throw from Weimar’s beautiful Park an der Ilm, the Bauhaus’ campus was housed within the two Art Nouveau buildings by Henry van de Velde, which are both designated as UNESCO World Heritage Sites due to their association with the Bauhaus. After the Bauhaus left Weimar for Dessau in 1925, these buildings continued to serve as a school for architecture and engineering during the Nazi period and after the wall. Right before the German reunification, the school reorganized and reclaimed its Bauhaus name and heritage as the Bauhaus-Universität Weimar. According to the school’s official website, the term “Bauhaus” represents “an eagerness to experiment, openness, creativity, and internationality.”

Since we visited Weimar in August, the university was not in session, so we got to roam the hallways without supervision. The beautiful central staircase has been beautifully restored to its former glory. On the sides of the main entrance are the busts of Henry van de Velde and Walter Gropius, the intellectual founders of the university here. More noteworthy, however, are two modernist wall reliefs: Configurations and Rhythm. The former was created for the famous 1932 Bauhaus Exhibition by Joost Schmidt, a master student with the Bauhaus in Weimar and Dessau. Weimar’s main campus building may not be as iconic as the Bauhaus building in Dessau, but it is here where the intellectual foundation of the Bauhaus was established.

With all of the classrooms and offices locked for summer recess, I actually spent some time perusing the student works exhibition in the hallways. I pity the students here for carrying the burdens from Bauhaus’s towering legacy. By coincidence, I discovered the famous Bauhaus murals on the side staircase. Also designed for the 1923 exhibition, the three murals were a wonderful manifestation of the Bauhaus’ Preliminary Course, particularly Wassily Kandinsky’s theory on the correlation between primary colors and basic shapes. In his mind, a dull shape like a circle should be represented by the color blue. The dynamic triangle is best suited for yellow, the most energetic color in the spectrum. Such an attempt at abstraction may seem overly simplistic by contemporary standards, but it does underscore the Bauhaus’s radical approach to art education.

I did notice a sign asking visitors not to go beyond the ground-floor foyer on my way out, so I apologize for inadvertently trespassing on campus after the fact. I noticed that the university offers regularly scheduled guided Bauhaus walks, but they are only available in German. On the guided tour, visitors should be able to visit Room 112, the former director’s office. Its interiors and furnishings were designed by Walter Gropius personally for the 1932 exhibition. From custom light fixtures, furniture, to rugs, this room represents the perhaps earliest example of comprehensive works of the Bauhaus and signified the works to come in Dessau.

While the main building is the star of the campus, visitors should not overlook the Van de Velde Building just opposite. Also listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the L-shaped building is well worth a visit because of the impressive murals by Oskar Schlemmer, the master of Bauhaus’s mural workshop and theater department. The murals at the top levels are particularly noteworthy. The intersecting figures are both static and dynamic. Schlemmer is almost known for his futuristic Bauhaus ballet and the school’s iconic logo.

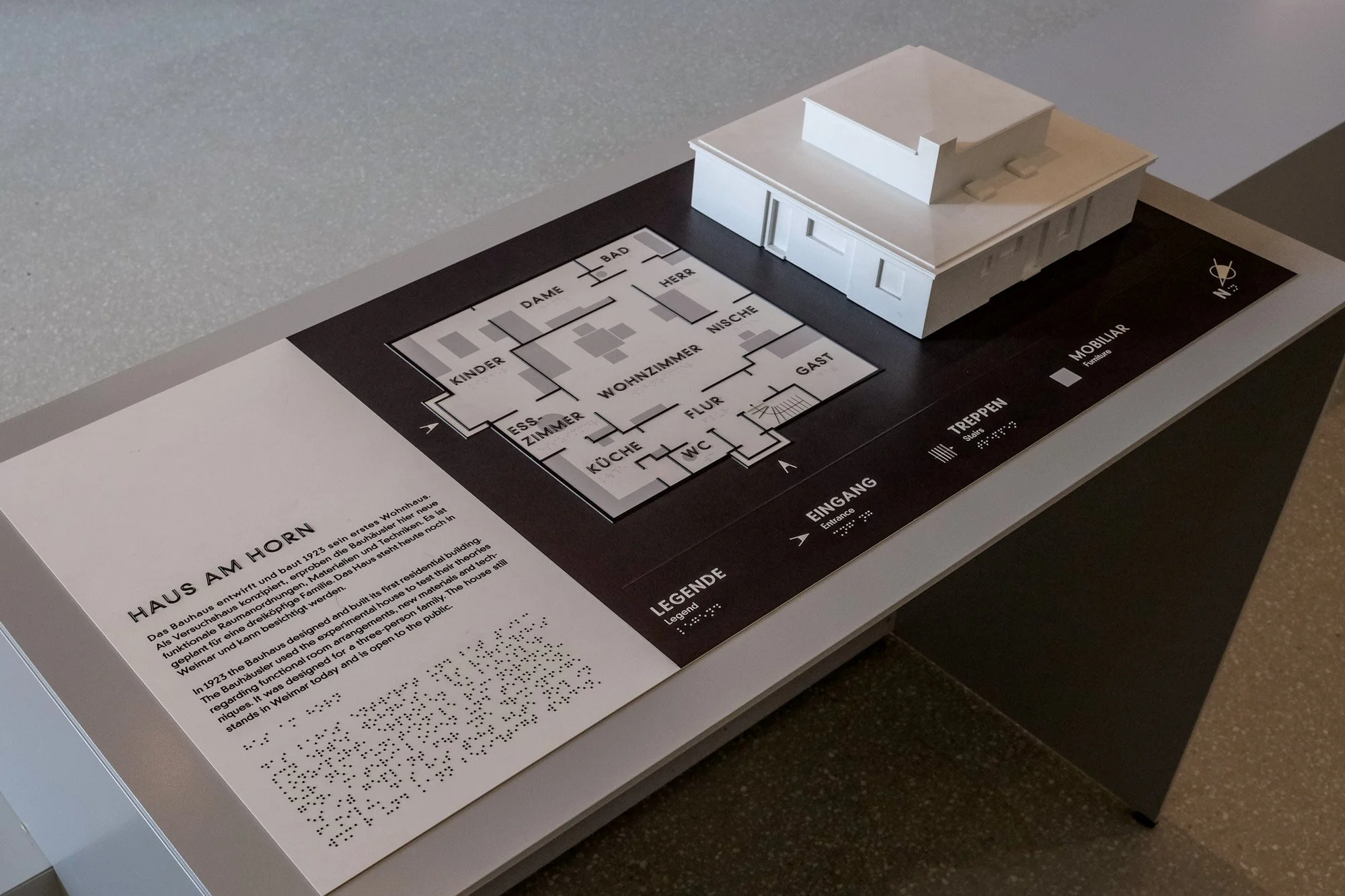

Haus am Horn

The architectural legacy of the Bauhaus was surprisingly sparse in Weimar. Because the Bauhaus regarded architecture as the pinnacle of art education, architecture had yet to become a primary subject of study during the school’s short tenure in Weimar. The one exception was Haus am Horn. By now, you may have noticed that the Bauhaus exhibition in 1923 was a pivotal event in the history of the Bauhaus. Only just a few years after the school’s founding, Gropius found that the political climate in Weimar had become increasingly hostile to his philosophy. Weimar has always been Germany’s intellectual capital and the city of Goethe and Schiller. Many residents found the Bauhaus to be too sharp a departure from the traditions of Weimar Classicism.

Since the Bauhaus received a substantial portion of its revenue from the State of Thuringia, the school agreed to host an exhibition to showcase its works and demonstrate their practical applications that could benefit Thuringia. Gropius had hoped the exhibition would guarantee the continuation of state support. The centerpiece of the exhibition was a house of modern living that could serve as a prototype for faculty housing. The student body voted to adopt a design by faculty member Georg Muche. True to the Bauhaus’ education mission, the students were actively involved in the house’s design development and construction.

Situated on an idyllic lot opposite the campus on the other side of Park an der Ilm, the house took four months to build and involved every department/workshop of the school. Objectively speaking, the architecture of Haus am Horn was far from impressive or inspiring. The simple square plans make the house look more like a municipal water station than a desirable residence. Brian was perplexed as to why I dragged him here and why this building could be a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Nicknamed Kaffeemühle (coffee grinder) at the time, the house surprised and conspired the public. It features an unordox layout, with the living room located at the center of the house, illuminated only by clerestories.

As much as I wanted to like the architecture of Haus am Horn, the highlights were the different furniture systems and built-ins in each room. Unfortunately, most of the original furnishings and accessories were lost. The project was financed by Gropius’s prior client, Adolf Sommerfeld. The house and all of its contents were transferred to Sommerfeld. The house was put on the market, and all the furniture was moved to Berlin. Over the decades, the house changed ownership several times and was threatened with demolition by the Nazis to make way for an Adolf Hitler School.

Fortunately, one of the house’s longtime tenants was Bernd Grönwald, a professor of architecture with political connections within the GDR. As an admirer of the Bauhaus, he spent significant efforts researching and restoring the house. Due to his dedication, the house was designated as a cultural monument of the GDR in 1973. He opened up his home for visitors and set up a permanent exhibit in the living room. The house was subsequently transferred to the university’s foundation and then to the Weimar Classicism Foundation in 2017. The house was fully restored for the Bauhaus’s centenary in 2019.

With much of the original furnishing lost, selected pieces were reconstructed in place to give visitors a better idea of the innovative design of the 1923 exhibition. One of the most lauded designs was the versatile furniture design and toys for the children’s room, designed by Alma Siedhoff-Buscher. Allegedly, Gropius was not overly pleased with the outsized attention she received, as he considered toy design and women’s work to be less industrious. Women actually comprised the majority of students in the early years of Bauhaus. The administration was concerned that the percentage of female students would somehow diminish the school’s prestige. A progressive institution like the Bauhaus certainly was not immune to sexism.

Of all the furniture pieces exhibited inside the house, the only piece original to the house was Marcel Brueuer’s dressing table for the woman’s bedroom. As we walked through the rooms, Brian couldn’t help remarking how much of the Bauhaus furniture looked like IKEA products. That was actually high praise, given Bauhaus’ influences on our contemporary consumer society. Although most of these items are meant for mass production, they were all handcrafted and are very precious as historic objects. Many of these early Bauhaus objects are concerned with construction technique rather than personal comforts. It was easy to forget everything we see here is essentially student projects.

Although many citizens of Weimar were curious about the Bauhaus’ works, most were puzzled and appalled by the unorthodox art education. While Weimar was governed by the left-leaning Social Democrats at the time of the school’s founding, the political winds changed quickly toward the far right. From a practical level, the exhibition backfired on the school. Soon after the exhibition ended, the state cut its funding for the Bauhaus by half and shortened the faculty’s contract term. With limited financial means, the school announced a planned closure in March 1925 and began looking for alternate sites and revenue streams. It ultimately led Bauhaus to the industrial city of Dessau, where the political climate was more favorable.

Bauhaus Museum Weimar

As much as I enjoyed the visit to Haus am Horn, I could envision many visitors would not be happy to pay for its €5 admission. Fortunately, the house was covered under either the all-inclusive Bauhaus Card or the Weimar Card. The other Weimar site covered under these cards is the Bauhaus Museum Weimar. Inaugurated just in time for the centenary of the Bauhaus, the museum is said to showcase the world’s oldest Bauhaus collection. With more than 13,000 objects, it is one of the five premier Bauhaus collections, with the other being the Bauhaus museum in Dessau, Berlin, and Tel Aviv.

The museum used to be located in the current home of the House of the Weimar Republic. Following an international competition, the realized design was by Berlin architect Benedict Tonon and Heike Hanada. Designing a museum for such a towering legacy is difficult. I hate to say it, but I can’t say I am in love with the architecture. The concrete cube felt oppressive and somewhat aloof to the urban fabric. Thankfully, in my opinion, the gallery inside is well-designed and presents the collection in a more approachable and enjoyable way compared to its counterpart in Dessau. Much to my surprise, the museum does not exclusively focus on the school’s time in Weimar.

While the museum in Dessau focused quite a bit on architecture, I can’t say that architecture makes the most exciting exhibit. In contrast, the exhibition on toys and theaters is far more interactive. They are probably the lesser-known works of the Bauhaus. Siedhoff-Buscher’s toys may not be realistic, but their abstract forms are revolutionary in encouraging children to assemble them. Predating the world-famous Lego system, these brightly colored designs are the vanguards of toy designs.

Speaking of Siedhoff-Buscher, women’s contribution to the Bauhaus was not often remarked upon. As mentioned earlier, Gropius was dismayed by the number of enrolled students and their impact on the school’s reputation. While most female students were allowed to participate in any disciplines, most were automatically assigned to weaving and printing workshops. Those who worked in a male-dominated field, such as a metal or joinery workshop, would have to prove themselves more to the male cohorts. Ironically, the one workshop that was most successful in commercializing their works and brought in the most revenue for the school was dominated by female students.

Naturally, our favorite sections are the Bauhaus’s furniture collection. On the second level, visitors were able to try out many of the most iconic chairs of the modern era. We were pleasantly surprised by how comfortable Marcel Breuer’s Club Chair is. Because Brian and I are in the midst of a home renovation, we were naturally drawn to the collection of hardware and fixtures. A couple of the most celebrated pieces, such as Professor Wilhelm Wagenfeld’s table lamp, are authorized reproductions on sale at the gift shop. If it were not for the exorbitant price tag, I was very tempted to pick up a couple of Theodor Bogler’s ceramic pottery containers he designed for Haus am Horn. As a vanguard of modernist design, the authentic Bauhaus design may be less refined than its mid-century successors.

The most successful Bauhaus objects may be the tea infuser set by Wolfgang Tümpel and Otto Rittweger. We actually owned a near-exact reproduction for years without realizing it originated from the Bauhaus. Brian typically does not care much about art movements, so I fully anticipated him to be completely bored. To my surprise, he actually heard of the Bauhaus before the trip because he works at a design/fashion school. Even if you have no interest in modernism, the legacy of the Bauhaus can be found in just about every aspect of modern life.